32 Short Story Collections That Will Cure Even The Worst Reading Slump

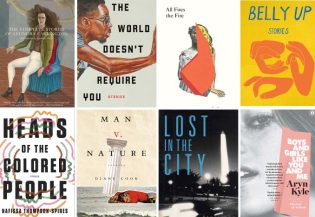

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington

I picked up this collection back in 2017 due entirely to the cover — the portrait of a wild-haired woman, the Jeff VanderMeer blurb (“This definitive collection … is a treasure and a gift to the world.”). Now it’s a book I regularly recommend as an all-time favorite. Carrington was a key creator in the Surrealist movement; her art and stories imagined beautiful, monstrous, and unwieldy worlds full of strange creatures and discomfiting interactions, often representative of her own mental illness. (Carrington was unwillingly admitted into a mental institution after a psychotic break during World War II, which she describes in the equally fantastic Down Below.) If you have a high threshold for weird — and/or if you loved Her Body and Other Parties — you should give this collection a try. —Arianna Rebolini

The World Doesn’t Require You by Rion Amilcar Scott

The stories in The World Doesn’t Require You all take place in the fictional town of Cross River, Maryland, built by the leaders of the country’s only successful slave revolt. Each story follows different enchanting residents — a struggling musician who is also the last son of God, a PhD candidate whose dissertation unwittingly sparks chaos, a robot; as a whole, the collection weaves incisive criticism, dark humor, and magical realism in profound explorations of belief, love, justice, and violence. —A.R.

All Fires the Fire by Julio Cortázar

The late Argentine writer Julio Cortázar is celebrated as a groundbreaking figure in Hispanic fiction for his use of the fantastical and his rejection of conventional narrative structure. This collection, originally published in 1966, makes clear why he’s so beloved. It opens with “The Southern Thruway” — a story about a traffic jam outside of Paris that ends up lasting for weeks, giving rise to ad hoc survival committees and alliances — and then jumps through space and time, from Cuban revolutionaries to Roman gladiators to a flight attendant obsessed with Greece. Each story is more compelling than the last — and if you think you know where any one is headed, you’re probably wrong. —A.R.

Belly Up by Rita Bullwinkel

Belly Up is an astounding collection of short stories — stories about girls who want to be plants, or a living boy who grew up in a family of zombies, or a dying woman who sneaks out for a night swim with an ailing man. These stories exist in worlds just past reality, just slightly uncomfortable, familiar until, suddenly, they aren’t. And I didn’t just read these stories, each revealing at once the absolute absurdity and magnificence of being alive; I savored them. Bullwinkel’s writing and world-building demand space to reflect on it, react to it, and then, if you’re like me, shout about it to anyone who will listen. —A.R.

Boys and Girls Like You and Me by Aryn Kyle

Putting together this list, I’m realizing I have something of a ~type~ when it comes to short stories — in a word, weird. This one is an entirely different flavor, no less delicious. These stories focus (in spite of the title) almost entirely on women and girls navigating all manner of relationships — a 9-year-old girl and her father’s new girlfriend escaping an uncomfortable birthday party; a young woman having an affair with her married boss — and Kyle depicts their desire, cruelty, and insecurity with heartbreaking clarity. —A.R.

Lost in the City by Edward P. Jones

Though perhaps best known for his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Known World, this 1992 story collection first put Jones on the map. Set in Washington, DC, back when it was known as Chocolate City, Jones’s stories feel vaguely folkloric in nature, even though they are about ordinary black folks, from a girl who is given a flock of pigeons to care for to a mother living in the house her drug-dealing son bought her. Suffused with a quiet sadness, these stories linger with you long after you’re done reading. —Tomi Obaro

Man v. Nature by Diane Cook

In a collection of short stories about all of the ways we define survival, Cook creates slightly off-kilter realities and the otherwise unremarkable characters who inhabit them — a miserly neighbor in a post-flood dystopia, 11-year-old boys who have been declared “not-needed,” a young woman whose house is swarmed after a span of good luck. It’s grim, violent, and darkly funny, but never so far removed from our most human urges to seem totally implausible. —A.R.

Heads of the Colored People by Nafissa Thompson-Spires

Thompson-Spires’ debut collection is a fearless exploration of race, identity, and class. The stories touch on the ways spaces and circumstances are coded (in one, a young girl tries to learn to be “more black” as a way to make up for her family’s upper-middle-class standing); Thompson-Spires deftly grapples with the pressures of being black in a country built around and for whiteness. It’s sharp, potent, and deeply felt. —A.R.

Read “A Conversation About Bread” from Heads of the Colored People.

What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah

A woman creates a sentient child out of hair trimmings. A rebellious high school senior living in the US is sent back home to Nigeria to live with relatives, where family secrets are unearthed. A woman with the ability to take people’s grief away grapples with the limits of her powers in a futuristic alternate universe devastated by climate change and war. The stories in this excellent 2017 collection are a mix of different genres — fantasy, realism, science fiction. What unites them is Arimah’s confident, innovative storytelling. Each story packs an emotional wallop. —T.O.

Large Animals by Jess Arndt

Arndt’s debut short story collection is provocative and haunting, forcing readers to reckon with their assumptions around gender and identity, masculinity and femininity, conformity, and queerness. Her narrators — each speaking in a frustrated but often hypnotic first person — travel through worlds that demand they subscribe to a system of categorization that simply doesn’t work for them; each story shows the internal and external manifestations of this conflict. There’s the parasite infecting a couple whose relationship is falling apart, the crystal cave one narrator refuses to leave, the beast that shows up nightly in the bedroom of another. It’s about the awkward absurdity of bodies, and Arndt is masterful in describing it with metaphor and ambiguity. —A.R.

A Lucky Man by Jamel Brinkley

Set predominantly in ’90s Brooklyn and the Bronx, A Lucky Man recognizes the stories to be told in banal disappointments — a failed marriage, a sick mother, an unrequited crush. Brinkley is a marvelous writer. The jaw of a man without his dentures looks like “a rotten piece of fruit.” There’s a solemn beauty to his writing, a clear sympathy for his characters, all of whom are vividly rendered. —T.O.

The Night in Question by Tobias Wolff

Tobias Wolff, along with writers like Raymond Carver, ZZ Packer, and Andre Dubus, is partly responsible for the 21st-century renaissance of the short story (though he’d probably disagree with a word so strong as ‘renaissance’). The Night in Question is his third collection, one of many remarkable works of his; Wolff is also a killer memoirist. What I love about Tobias Wolff is his intimate portraits of family life set against terrifying and complex macro backdrops, from wars to great sweeps of generational change. He’s got a deceptively simple style that, combined with his incredible talent at character development over just a few small pages, has often brought me to tears. I’ll be revisiting his work in lockdown; these are stories that make you believe in a life fully lived. —Shannon Keating

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang

Zhang’s debut story collection is at once explicit and poignant, vulgar, and refined — equal parts pain and beauty. Each story centers a young, first-generation Chinese American woman narrator, each with a distinct voice but overlapping in experience (most show up in each other’s stories) and linked by the loyalty, guilt, and love that comes with knowing how much, and how continuously, one’s parents have sacrificed. The weight of these conflicting emotions pulls on Zhang’s narrators and her writing, often in accelerating run-on sentences — but the headiness is balanced by Zhang’s incorporation of the (often grotesque) physical realities of being a human being. It’ll make you laugh, it’ll make you cry, it’ll make you gag, but you’ll love all of it. —A.R.

All Roads Lead to Blood by Bonnie Chau

Chau’s exhilarating debut probes the lives of second-generation Chinese American women, especially focused on dating and sex — their disruptive hookups, tiring long-term relationships, their search for something meaningful. Throughout, Chau writes sexuality in a way both vivid and new (see: “Pants and skirts were shrugged, scooted down, buttonholes were stretched into O’s like gasping mouths, then relieved of their charges”), and her stories are honest and arresting. All Roads Lead to Blood will ring true to anyone who feels like they’re lingering on the path toward figuring themselves out. —A.R.

Sooner or Later Everything Falls Into the Sea by Sarah Pinsker

Pinsker’s debut short story collection is speculative and strange, exploring such wide-ranging scenarios as a young man receiving a prosthetic arm with its own sense of identity, a family welcoming an AI replicate of their late Bubbe into their home, and an 18th-century seaport town trying to survive a visit by a pair of sirens — all while connecting them in a book that feels cohesive. The stories are insightful, funny, and imaginative, diving into the ways humans might invite technology into their relationships. —A.R.

The Dark Dark by Samantha Hunt

Samantha Hunt’s stories are about metamorphosis — physical, psychological, fantastical, life-changing. There’s the FBI agent who ruins his own mission by falling in love with a military robot; the woman who can’t stop cheating on her husband every time she shifts into a deer; the wife who, after months of no sex, starts to wonder if her husband is even real. Hunt writes about women’s relationships to their bodies and their realities, their trust in themselves, and she does so with such sharp writing, and within such beguiling worlds, that The Dark Dark becomes impossible to put down. —A.R.

The Elephant Vanishes by Haruki Murakami

This collection wasn’t on my radar until I saw (and became obsessed with) the 2018 movie Burning and found out it was based on “Barn Burning” — a short story in a Murakami book I’d somehow never read. Luckily I fixed that problem. The 17 stories in The Elephant Vanishes are imaginative, eerie, provocative, and sardonic; they follow a woman who hasn’t slept in 17 days, another who’s courted by a monster in her backyard, a couple who decide to rob a McDonald’s, to name a few. It’s everything we love about Murakami, in bite-size pieces. —A.R.

Birds of America by Lorrie Moore

Lorrie Moore, whose (also excellent) early work inspired a generation of young writers to abuse the second person, is a veritable master of the short story. Her third collection, Birds of America, is arguably her best, but you wouldn’t go wrong if you were to pick up her full collected stories, published in 2008. What’s so compelling about Moore’s work — besides her sometimes lyrical, sometimes straightforward, but always gorgeous prose — is that she manages to make you laugh and make you completely, existentially devastated in the span of a single paragraph. Her stories are, to borrow a name of one of her collections, Like Life: miserable, hilarious, morally ambiguous, lovely, mundane, profound. —S.K.

Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage by Bette Howland

For the inaugural title of their new book publishing imprint, literary magazine A Public Space released Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, a collection of the late Bette Howland’s autobiographical short stories spanning the entirety of her career. Howland’s writing — notably lauded by Saul Bellow — is rich with wry observations and humility, drawing from her experiences as a self-identified outsider: a divorcé and single mother whose family disapproved of her; a writer and artist fighting poverty, self-doubt, and mental illness in working-class Chicago. —A.R.

Lot by Bryan Washington

Washington’s debut short story collection is an ode to Houston and a vibrant portrait of the myriad people who call it home. The stories circle around a young boy figuring out his sexual identity while holding down a job at his family restaurant; around him, a city of creators, survivors, and hustlers vibrates with life. Washington’s effervescent prose draws the reader into the fold — his use of first person, especially plural first, can read like a generous inclusion — as his characters explore family, community, new freedoms, and love.

The Complete Stories by Flannery O’Connor

It’s hard to talk about short stories without bringing up Flannery O’Connor — one of the truly great American short-story writers of the 20th century. Her works are dark and disturbing commentaries on ethics in Middle America as she weaves grotesqueries out of the traditional “moral at the end” short stories that are typical of the genre. The Complete Stories, for which O’Connor posthumously won the National Book Award, is a great intro to some of O’Connor’s most famous stories and lesser-known works, too. —Jillian Karande

Sansei and Sensibility by Karen Tei Yamashita

Karen Tei Yamashita contends with the Western canon in this astute, pitch-perfect, and wryly funny short story collection. Yamashita recasts Jane Austen characters as Japanese Americans navigating themes familiar to anyone who has read Austen and her contemporaries — social tension, familial obligation, clumsy personal growth, all of the mundanities that add up to meaning — through the lens of Japanese immigrant and Japanese American experiences. It’s a genuine pleasure to read. —A.R.

Drinking Coffee Elsewhere by ZZ Packer

Hilarious and exquisitely written, this story collection released in 1997 immediately established Packer as one of her generation’s premier writers of short fiction. And it’s easy to understand why. From dueling Brownies troops in the first story to the darkly funny title story about a black student attending a predominantly white college, her stories plumb both the absurdity and the isolation inherent in belonging to the shrinking black middle class. —T.O.

Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self by Danielle Evans

Girls suffer through growing pains in this fantastic debut collection published in 2010. A biracial preteen spends the summer with her white grandmother and cousin, learning more about the frosty relationship between her grandmother and her mother. A college student deals with an unexpected pregnancy. The main appeal of these stories lies in the pleasure of Evans’ writing. Her prose is both wickedly funny and subtly devastating. —T.O.

Five-Carat Soul by James McBride

Five-Carat Soul covers a lot of ground, all of it unpredictable, exhilarating, and, often, hilarious. The short stories bounce from one unlikely protagonist to the next — from the antique toy dealer chasing a legendary train set owned by Robert E. Lee, to a captive lion making sense of the hierarchy of the zoo, to the one and only Abraham Lincoln — and each story, despite the foreignness of its characters’ circumstances, expertly weaves in timeless themes. I love these stories individually, but all together they make for a wild and utterly delightful ride. —A.R.

White Dancing Elephants by Chaya Bhuvaneswar

Bhuvaneswar is a *force* in her provocative debut, which centers on women of color who resist easy categorization — a therapist who is drawn to but disgusted by her young patient, a scholar desperate to justify her affair with her terminally ill best friend’s husband, a woman remembering the girlfriend she abandoned when she accepted her arranged marriage. Bhuvaneswar fully inhabits them, breathing life into their dissonant, beautiful, complete selves. —A.R.

Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

Reading Friday Black is like being shaken awake. These stories exist in a sort of hyperreality — ordinary characters living in the not-so-unbelievable, Black Mirror–esque future of a culture that doesn’t hesitate to commodify cruelty or monetize revolution. (See: “Zimmer Land,” the story about an amusement park that allows guests to play-act their most violent urges.) Adjei-Brenyah skewers the ways we brush past racism and injustice, making the absurdity of the rhetoric around both impossible to ignore. —A.R.

Sabrina & Corina by Kali Fajardo-Anstine

Set against the background of Denver, these stories follow indigenous women in relation to their home. In some cases the land holds histories these women long to escape; in others, it changes so rapidly as to disorient those who call it home. Fajardo-Anstine’s prose blossoms on the page; her scenes and characters develop so vividly that they’re likely to leave an impression lasting long after you stop reading. —A.R.

Evening in Paradise by Lucia Berlin

Berlin’s first posthumous collection, A Manual for Cleaning Women, got a lot of (deserving) praise, but I’m partial to the followup. Here we see Berlin’s world — her time spent in Texas, Chile, and Mexico — filtered through evocative fiction. Her characters are utterly captivating — the moneymaking kids, the retired ambassador, the musicians, the actors, the addicts — and her scenery envelops you. But it’s the early stories, those that follow the meandering adventures of kids just trying to fill their days, that are most vibrant. —A.R.

Fly Already by Etgar Keret

Keret’s stories range from dark to downright silly — there’s the child in the title story who misunderstands the intentions of a man standing on the roof of a tall building, the strangers who meet up daily after work to share a joint on the beach, the increasingly absurd email exchange between a man desperate to bring his mother to an escape room that is unfortunately closed, and the owner of said escape room with a pretty big secret to hide. Each is beautifully wrought and rife with meaning — and slightly maddening in its ambiguity. —A.R.

The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges

If even the prospect of short stories seems overwhelming, I recommend one of my most comforting reads — a book that is perfect if you want nothing more than to be swiftly and briefly transported to a more magical reality. The Book of Imaginary Beings is an encyclopedia of 116 “strange creatures conceived through time and space by the human imagination,” both general (e.g., dragons) and specific (e.g., the Cheshire Cat). Forget about sitting down with it for a large chunk of time — it’s better when you dip in and out. —A.R.

Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado

There’s a reason this book was everywhere — it’s really very good. Machado’s sharp, eerie, and often hilarious stories experiment with format in a way that feels genuinely new, dropping in theatrical asides to the reader, or structuring a narrative around Law and Order episode titles. Their darkness is playful until it’s not, and that tipping point happens whenever the reader realizes the surrealist nightmares Machado has built around her female protagonists — worlds in which women’s bodies are infected by the trauma they’ve witnessed, or made vulnerable by an epidemic of becoming ethereal — aren’t quite so fantastical at their cores. If you haven’t read it yet, now’s the perfect time. —A.R.